Researchers at Ryerson University in Toronto want to use virtual reality to learn more about the so-called Messy Syndrome in order to develop new therapies. As part of a study, they are confronting messies and healthy people with virtual clutter and comparing their reactions.

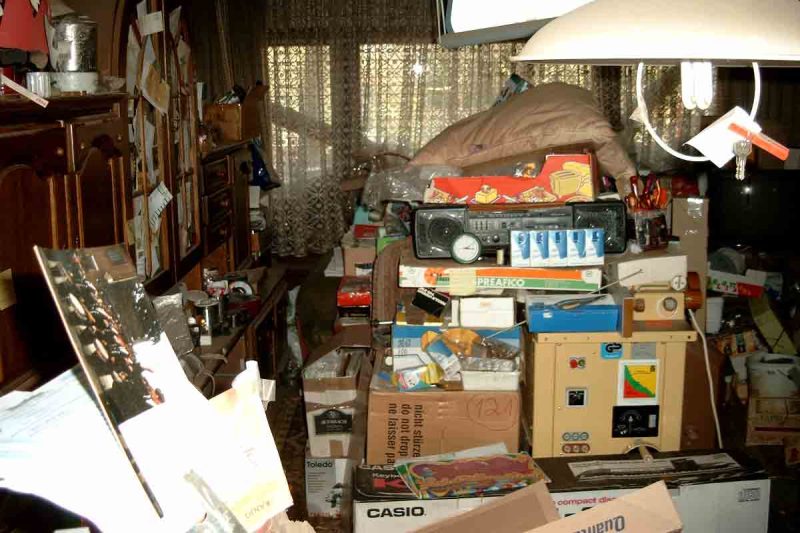

Messie syndrome is one of the poorly researched mental disorders. The illness manifests itself in people losing the ability to judge the value of objects. Because they find it difficult to part with objects, they hoard more and more clutter. Many messies do not seek help because they fear social stigmatisation by other people. Apart from traditional psychotherapy, there are hardly any treatment methods.

VR study shows: Messies suffer from clutter

The latest study by Ryerson University in Toronto on this topic consists of three VR experiences in which both people with and without symptoms take part. The participants' reactions and stress levels are measured and the results are then compared with each other.

In the first VR experience, the study participants find themselves in a virtual room that gradually fills up with clutter. The experiment revealed that, contrary to expectations, messies do not cope better with the growing clutter, but on the contrary react more negatively than the other study participants. "People who live in such environments suffer more than we realise," concludes Hanna McCabe-Bennett, who led the study.

Next, the participants were confronted with two 360-degree images under the VR glasses. The first was designed to evoke negative or neutral feelings, while the second showed a second-hand shop. The experiment was designed to show whether a hoarder is more inclined to buy old items.

In the final VR experience, the study participants were placed in a virtual office full of clutter, where they could move around freely and interact with the objects. After this experiment, the participants had to list the objects they had seen and make suggestions on how to organise them. This was to test the memory of messies and whether they have greater difficulty categorising objects.

Personal trauma as a cause

McCabe-Bennett explains that messies often hoard objects because they are afraid of losing the memories associated with them. "They think they need these objects to evoke fond memories."

Tellier, a participant with the Messy Syndrome, told the study leader the reason why she hoards objects: When she was a child, her parents separated. On the day she had to pack her things and move away with her sister and mother, she could only take one suitcase with her and had to leave everything else behind.

"The VR glasses help me to overcome my attachment to objects. They allow me to see them as they really are. I can take a step back," says Tellier.

For McCabe-Bennett, the study primarily serves to understand the disease. In a second step, the results should help to develop VR treatment methods. One possibility would be that sufferers could learn to gradually detach themselves from the worthless objects in VR simulations of their own living space.

Source: Vrodo